Steady ground is fundamental to happiness, and few concerns outweigh the worry for a safe and stable world, one where our chances of a prosperous life are high. Over time though, concerns we have for the planet and our loved ones will be repeatedly and often radically reimagined.

Without exception, the way we frame our worldview underpins the rationale for believing that we lead a happy or unhappy life. The weight of the world works in the same way—you are either certain or uncertain about Earth’s future, and that shapes where your feelings land.

If we knew exactly when Earth’s life-giving forces would collapse, would that knowledge leave our spirits broken—or liberated from having to speculate? Imagine being blindsided by a cosmic event that shreds our atmosphere, disrupting weather, animal migrations, and global communication.

Would you begin living differently because it was actually happening, or are you already living in anticipation of change—planned or not, pleasant or otherwise? Stoicism embraces acceptance, spending energy only on what helps. In this, mindful living offers a path to peace.

Acceptance doesn’t mean inaction. A calm mind can still raise a banner, plant a seed, or build a shelter. If runaway greenhouse gases were to cause a global famine, our response would become a legendary battle—not just for survival, but for dignity. In that battle, what would your role be? And if you died of old age, would people remember you as a weary witness—or a joyful fighter?

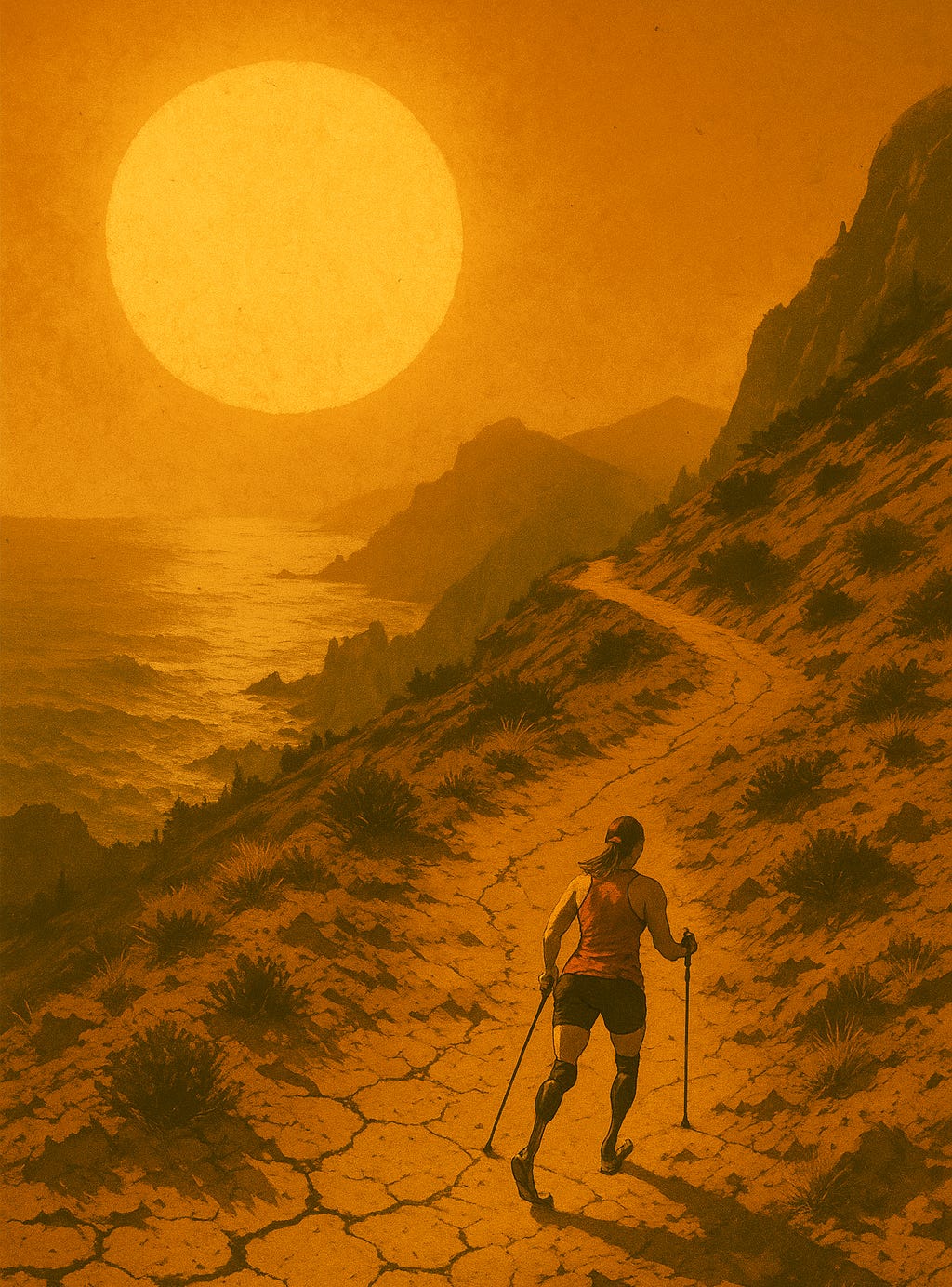

I know a joyful warrior.

Felicia is one of the most upbeat people I know. When she lost her legs to sepsis, she continued to live as positively as ever—competing three times in the Paralympics. At Paris 2024, she helped Canada win Bronze: its first-ever medal in sitting volleyball. If the world was ending, I think she’d happily try to save us.

Not everyone has Felicia’s resilience—but everyone has some kind of power to act. For some, it’s time. For others, it’s influence, wealth, or access. Those with resources to spare can use their clout to invest in meeting the needs of the rest of the planet. We shouldn’t shame people for simply having wealth, but we can pay attention to how they use it—taking comfort knowing a billionaire can only eat so many steaks.

A dear friend once shared his belief that the world’s problems were driven by sociopaths, greed, and unchecked power—people who must be stopped for humanity to thrive. It was a feeling rooted in pain, and a deep longing for a kind and joyous world. We talked for a long time about what or who needed confronting, and how that would ever come about.

I offered a different view—something like a gardener choosing not to fight weeds harder, but instead improving the conditions so that weeds simply don’t thrive. Rather than fixating on destruction, we might focus on the ecology we can shape. Agency doesn't always look like resistance; sometimes it looks like nourishment.

I’ve spent years reflecting on these questions—how much power we have, and what kind of world we’re cultivating with it. I remember watching the North Shore mountains lose their snow earlier each spring, and hearing ski resorts report negative impacts on their operations. Cherries and other flowering fruit trees blushed with blossoms earlier than in years prior. Our fig trees produced ripe fruit nearly three times in a single year.

These trends didn’t move in just one direction. Some reversed, some worsened, and the only thing that remained consistent was how unpredictable everything became. Today, farms of all sizes face the challenge of adapting—reducing reliance on chemicals, managing new weather patterns, and stretching increasingly uncertain water supplies.

In BC, I learned that most fruit entered the supply chain through just two major packing companies. While roadside stands still exist—and carry a certain romance—they’re typically just a small outlet, not a practical channel for moving half a billion dollars’ worth of produce.

We’re seeing more than weather change—we’re watching the systems meant to manage food and land begin to fracture. And in the midst of that, cooperation remains our best tool: between suppliers, workers, and consumers alike.

So what does agency look like now?

If we shop consciously, we can begin to trace where our materials come from. Even in our own home gardens—who supplies the soil, the water, the seeds, and the tools? When we order food from restaurants, where do they source their ingredients?

These aren’t small questions. They’re invitations. We can adapt—but doing so may reduce efficiency, especially as we transition to new methods. Poor production years may bring higher costs, lower quality, or even shortages that force us to let go of certain comforts.

Still, having citizens meet their own needs—and those of their communities—isn’t a fantasy. It’s already happening. Secondary producers add resilience every day, buffering us against threats like pests, bad weather, and economic shocks.

Our power doesn’t rest with a few who make decisions for us—it’s in the thousands of everyday actions, like butterflies choosing to flap their wings. That same mindset can extend beyond food. The materials we use daily, the goods we depend on—they all have origins. And so do the people who bring them to us.

Need by need, we can trace what we use, connect with the humans who provide it, and learn how they draw from the Earth we all share.

Happy battling, joyful warrior.